Rails from Request to Response: Part 1 - Introduction

27 Dec 2013

I’ve been developing Rails applications for personal and work projects for several years now, and I recently realized that my understanding of the Rails internals was relatively limited. I’m totally comfortable wiring up routes and controllers and working with all of the MVC goodness that comes with Rails, but I didn’t really understand how it all tied together under the hood. I decided to change this by diving into the Rails source code to really understand what happens from the point that a request comes in to when a response is rendered and sent back. The result is a series of posts with some findings that I hope will be interesting and informative to anyone who works or has worked with Rails.

The Setup

I set up an incredibly simple Rails 4 app running a forked version of Rails 4.1.0.beta cloned from GitHub at 0dea33f770. For the web server, I used Unicorn at 728b2c70cd. The application consists of a single PostsController with an index action that displays all posts in the database - nothing too interesting, as this series is focused entirely on the internals of Rails.

Note that this series assumes a reasonable level of familiarity with Ruby and Rails MVC. There’s a bunch of code examples, but this is mostly because I like digging through code and not because it’s crucial to understand every single line. The goal here is to understand how all of the pieces fit together at a high level and shed some light on what’s going on behind the scenes.

Servers

Before jumping straight into the Rails stack, it’s worth at least mentioning the roles of various servers. I’m going to gloss over app servers such as Thin or Unicorn (and entirely skip web servers like nginx). These are crucial components of the request-response process, but this series is mostly about the Rails side of things. However, I’ll include a brief example with Unicorn as it’s an interesting way to see the entry point of a Rails app.

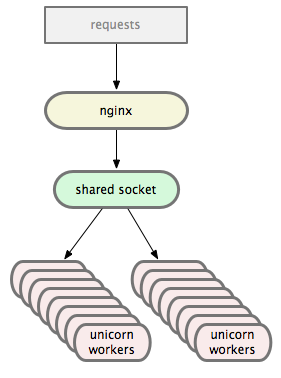

The Unicorn Architecture

Unicorn is a preforking application server that conforms to the Rack interface, where preforking means that it uses forked worker processes to concurrently handle requests. When it starts up, the master process loads our Rails application code into memory, forks some number of workers, monitors them, and traps incoming signals (such as QUIT, TERM, USR1 and so on, which are used for tasks such as shutdown and configuration reloading). The workers are responsible for the actual handling of requests. Here’s a diagram of the Unicorn architecture (taken from this excellent post on Unicorn from GitHub):

The workers read incoming HTTP requests off of the shared socket, send them into the Rails application, and write back the received response, which is typically a fully rendered layout+view. Most of this happens in the #process_client method of Unicorn’s HttpServer class - here is the relevant code:

# unicorn/lib/unicorn/http_server.rb

def process_client(client)

status, headers, body = @app.call(env = @request.read(client))

...

http_response_write(client, status, headers, body,

@request.response_start_sent)

client.shutdown

client.close

rescue => e

handle_error(client, e)

endI omitted some code related to HTTP 100 status processing and Rack socket hijacking - you can read the method in its entirety here. However, we can see that the core of the method is extremely simple! The first line is the Rack specification at work - according to the specification, a Rack app is simply a Ruby object that responds to #call and accepts an environment hash (env), and returns an array of [status, headers, body]. This simple format is what’s at the heart of ‘Rack-compatible’ frameworks such as Rails, Sinatra, Padrino, etc. Back in the #process_client method, we can see then that we’re simply calling our Rack app @app with the env environment hash, and writing back the response before closing out the client. Unsurprisingly, @app is our Rails app - an instance of Rails::Application. If you look in config/application.rb in your Rails project, you can see its definition:

# blog/config/application.rb

module Blog

class Application < Rails::Application

...

end

endSo there’s our entry point into the Rails stack! However, if you look closely, #call is not defined in Blog::Application. It lives in the definition of its parent class, Rails::Application. From here, we need to understand the Rails application hierarchy and how our request gets handled internally.

Rails Applications and Engines

As we mentioned before, the #call entry point of our Rails application is defined internally within Rails, in the Rails::Application class. Here’s its definition (source here):

# rails/railties/lib/rails/application.rb

module Rails

class Application < Engine</br>

# Implements call according to the Rack API. It simply

# dispatches the request to the underlying middleware stack.

def call(env)

env["ORIGINAL_FULLPATH"] = build_original_fullpath(env)

env["ORIGINAL_SCRIPT_NAME"] = env["SCRIPT_NAME"]

super(env)

end

...

end

endNot a lot going on here - mostly just a call to super. If we keep traversing, we see that the Rails::Application class inherits from the Rails::Engine class. If you’re familiar with Rails engines, which are like mini-applications that provide functionality to their host applications, it’s fascinating to note that a Rails::Application is really just a supercharged engine!

Let’s look at #call in the Engine class:

# rails/railties/lib/rails/engine.rb

module Rails

class Engine < Railtie

def call(env)

env.merge!(env_config)

if env['SCRIPT_NAME']

env.merge! "ROUTES_#{routes.object_id}_SCRIPT_NAME" => env['SCRIPT_NAME'].dup

end

app.call(env)

end

...

end

endSo the Engine class inherits from Rails::Railtie. Looking at the source, we see that the Railtie is the core of the Rails framework, and provides hooks for things such as initializers, config keys, generators, and rake tasks. Every major Rails component (ActionMailer, ActionView, ActionController, and ActiveRecord) is a Railtie, and this mechanism lets you swap components in and out as you please.

In the Engine’s #call method, we see another delegation of #call - what is app in this context? If we look in the same file, we find:

# rails/railties/lib/rails/engine.rb

# Returns the underlying rack application for this engine.

def app

@app ||= begin

config.middleware = config.middleware.merge_into(default_middleware_stack)

config.middleware.build(endpoint)

end

endNow we’re getting somewhere. The engine builds a middleware stack as a Rack application (where endpoint is our application’s routes, an instance of ActionDispatch::Routing::RouteSet - more on that in the next post!), and delegates #call to it. Rack middleware is a way of ‘filtering’ requests and responses, and separate the stages of request processing into a pipeline - for example, handling authentication, caching, and so on. You can see the list of middleware used by the application by running rake middleware: - here’s what I see when I run that in the Blog application:

$ RAILS_ENV=production rake middleware

use Rack::Sendfile

use \<ActiveSupport::Cache::Strategy::LocalCache::Middleware:0x007f7ffb206f20\>

use Rack::Runtime

use Rack::MethodOverride

use ActionDispatch::RequestId

use Rails::Rack::Logger

use ActionDispatch::ShowExceptions

use ActionDispatch::DebugExceptions

use ActionDispatch::RemoteIp

use ActionDispatch::Callbacks

use ActiveRecord::ConnectionAdapters::ConnectionManagement

use ActiveRecord::QueryCache

use ActionDispatch::Cookies

use ActionDispatch::Session::CookieStore

use ActionDispatch::Flash

use ActionDispatch::ParamsParser

use Rack::Head

use Rack::ConditionalGet

use Rack::ETag

run Blog::Application.routesWe’ll skip over most of these, and it’s not required to understand each and every one, although it’s important to note that when a request comes in, it will start with the first piece of middleware in the list and move down going through each one until it finally reaches your application’s routes in Blog::Application.routes.

At this point we’ve concluded our introductory look at the app server / Rails application stack and entered the Rails routing/dispatch stack, which we’ll examine in the next post. Stay tuned!

Tweet