Rails from Request to Response: Part 3 - ActionController

02 Jan 2014

This is part 3 of a series taking an in-depth look at how the internals of Rails handle requests and produce responses - be sure to catch up on previous parts!

- Part 1 - Introduction + Unicorn

- Part 2 - Routing

Last time we focused on how requests are routed to controller actions through Journey and the ActionDispatch stack. This time, we’ll look at ActionController and how controller actions turn into a rendered view.

The last post ended with the #dispatch method of the ActionDispatch::RouteSet::Dispatcher, which actually calls the controller action. Here’s that method as recap:

# rails/actionpack/lib/action_dispatch/routing/route_set.rb

def dispatch(controller, action, env)

controller.action(action).call(env)

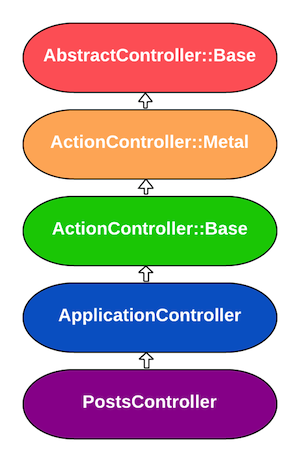

endRemembering that controller is a class reference such as PostsController, we need to find the definition of the class method action. That’s actually defined in the ActionController::Metal class, so before we look into that, let’s go over the controller hierarchy. In this series, we’ve been working with a simple PostsController that inherits from the ApplicationController, a pretty standard setup for most Rails controllers. However, there’s several more levels to the controller hierarchy. If we take a look at app/controllers/application_controller.rb, we see that it inherits from ActionController:Base, which itself has several parent classes. Here’s what the whole chain looks like:

Click for larger image

The bottom two are user-facing classes, while the top three are internal to Rails. Let’s examine them top down. The root, AbstractController::Base, is a self-proclaimed low-level action API that should not be used directly. Its subclass, ActionController::Metal provides the simplest-possible Rack interface, without all of the helpers you get from ActionController::Base. From the docs, a metal controller allows us to write something like:

class HelloController < ActionController::Metal

def index

self.response_body = "Hello, world!"

end

# And in config/routes.rb:

get 'hello', to: HelloController.action(:index)So as we saw before, metal controller actions act as extremely simple Rack endpoints. It’s not until we get down to ActionController::Base that we get all the goodies such as rendering helpers, cookies, flashes, instrumentation and more (in fact, if you look at the source for the class, you’ll see it’s mostly just including a ton of modules!).

We’ll dive into ActionController::Base in great detail later, but in the meantime let’s return to the action dispatch code we saw previously. The action method which was called is defined in the ActionController::Metal class, and returns a Rack endpoint. Here’s its definition:

# rails/actionpack/lib/action_controller/metal.rb

def self.action(name, klass = ActionDispatch::Request)

middleware_stack.build(name.to_s) do |env|

new.dispatch(name, klass.new(env))

end

endHere, middleware_stack is a class attribute that’s an instance of ActionController::MiddlewareStack. In the block passed to middleware_stack#build, we create a new controller instance and call its dispatch method, passing in the name of the action, and an ActionDispatch::Request constructed from the current environment hash. In our simple app example, the middleware app is actually empty so #build just returns the block we passed in (recall that the RouteSet #dispatch method invokes this block with controller.action(action).call(env)).

The #dispatch method invoked on the controller instance first goes through the RackDelegation module, which is included by ActionController::Base:

# rails/actionpack/lib/action_controller/metal/rack_delegation.rb

def dispatch(action, request)

set_response!(request)

super(action, request)

endAll we’re doing here is initializing the internal @_response instance variable to a new ActionDispatch::Response in set_response! and calling super, which takes us up to the #dispatch method in ActionController::Metal.

# rails/actionpack/lib/action_controller/metal.rb

def dispatch(name, request)

@_request = request

@_env = request.env

@_env['action_controller.instance'] = self

process(name)

to_a

endSo we set some instance variables, call process, and return to_a, which returns our beloved [status, headers, response_body] trio. The #process method takes us back up to AbstractController::Base, where we first call #process_action:

# rails/actionpack/lib/abstract_controller/base.rb

def process(action, *args)

@_action_name = action_name = action.to_s

unless action_name = method_for_action(action_name)

raise ActionNotFound, "The action '#{action}' could not be found for #{self.class.name}"

end

@_response_body = nil

process_action(action_name, *args)

endmethod_for_action checks to see if the action is actually defined in the controller, and in the case it returns nil we get an ActionNotFound error.

process_action

The call to #process_action kicks off a fairly complex series of method calls that traverses a large class/module hierarchy. ActionController::Base includes a large number of modules that define the #process_action method, which do some work and then call super. Here’s a snippet of code from the ActionController::Base class (comments from source):

# rails/actionpack/lib/action_controller/base.rb

module ActionController

class Base < Metal

MODULES = [

# (n.b. bunch of modules omitted here ...)

AbstractController::Callbacks,

# Append rescue at the bottom to wrap as much as possible.

Rescue,

# Add instrumentations hooks at the bottom, to ensure they instrument

# all the methods properly.

Instrumentation,

# Params wrapper should come before instrumentation so they are

# properly showed in logs

ParamsWrapper

]

MODULES.each do |mod|

include mod

end

end

end(you can see a list of all the modules included here.)

It helps here to have an understanding of how including a module affects the ancestor chain in Ruby. In short, including a module into a class actually inserts that module as a direct superclass of the including class, with the module’s superclass set to the original parent class, thus preserving the method lookup chain. I put together this gist as a simple example to help visualize the call stack. This means that method calls will proceed backwards up that list: #process_action in the ParamsWrapper module will come first, followed by Instrumentation, Rescue, and AbstractController::Callbacks before finally arriving at AbstractController::Base#process_action. I’ll gloss over each step, but the source is recommended reading for anyone looking to understand deeply - all of the modules live in the actionpack/lib/action_controller/metal directory in the Rails source.

The ParamsWrapper module wraps parameters into a nested hash, with the key name matching the controller’s name. For example, if you’re POSTing to the UsersController, you can just use data like

{"name": "Bob"}and it will automatically be wrapped into

{ "user" => {"name" => "Bob"} }The Instrumentation module provides pub/sub hooks into controller action processing (which will come up later in this post) using ActiveSupport Notifications, as well as including some view runtime benchmarking information. I recommend the Rails Guide on the notification/instrumentation system for more information.

#process_action in the Rescue module wraps the call to super in an exception handler, and enables the rescue_from helpers.

The AbstractController::Callbacks module uses ActiveSupport’s callback mechanism to hook into #process_action - this is where before/after filters (before_action and after_action in Rails 4 terminology) are run. Defining a before/after/around filter simply inserts the method as a callback to be executed. Here’s what that looks like:

# rails/actionpack/lib/abstract_controller/callbacks.rb

module AbstractController

module Callbacks

include ActiveSupport::Callbacks

def process_action(*args)

run_callbacks(:process_action) do

super

end

end

end

endFinally, ActionController::Rendering defines #process_action in order to set the request formats (such as :html or :json).

Here it’s worth mentioning the ActionController::LogSubscriber. This uses the ActiveSupport notification system mentioned previously to hook into several events such as start_processing.action_controller and process_action.action_controller (both of which are triggered in the Instrumentation module). This is what’s responsible for generating the log messages such Processing by PostsController#index as HTML or Completed 200 OK in 27ms. You can find its source here.

At this point, we’ve made our way through the entire module chain and arrived at AbstractController::Base#process_action, which is refreshingly simple:

# rails/actionpack/lib/abstract_controller/base.rb

def process_action(method_name, *args)

send_action(method_name, *args)

endOf course, send_action goes through a module chain of its own! Don’t panic - only one module in ActionController::Base defines send_action - the ActionController::ImplicitRender module. It’s pretty simple:

# rails/actionpack/lib/action_controller/metal/implicit_render.rb

module ActionController

module ImplicitRender

def send_action(method, *args)

ret = super

default_render unless response_body

ret

end

...

end

endThis module is what lets you write controller actions without an explicit call to render - it causes the view matching the action to be rendered, assuming no render has been performed already. This also handles the case if there is a template without a corresponding action. The call to super in the method goes up to AbstractController::Base#send_action, which is just an alias for send - finally we’ve actually called the controller method!

Conclusion

This is all a lot to take in - to recap, we’ve covered:

- The

ActionController/AbstractControllerhierarchy - How

ActionController::Metalprovides a barebones Rack action interface - How

ActionController:Baseincludes a ton of modules that provide useful features such as parameter wrapping and before/after filters by implementing#process_action - How views get rendered by default without having to call

renderin the controller every time, thanks to theImplicitRendermodule

At this point in the series, we’ve seen everything from reading clients from a socket, sending the request into Rails, the routing process, and controller dispatch. In a future post we’ll examine ActionView and the view rendering process!

Tweet